Erica Cardwell

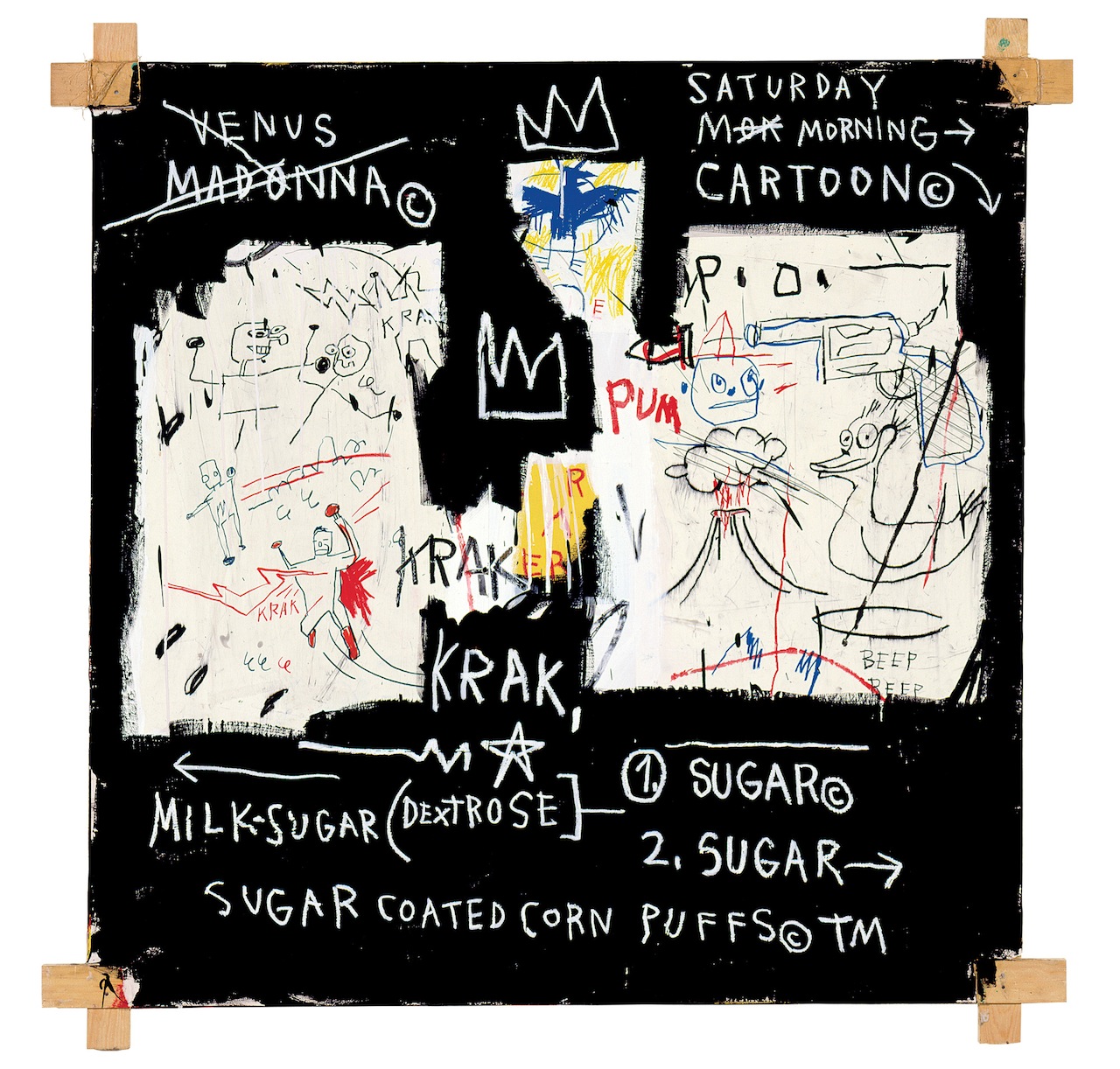

Jean-Michel Basquiat, “Untitled” (1981), acrylic and oilstick on canvas, 244.48 x 182.88 cm, Eli and Edythe L. Broad Collection (photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles, © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat [2014], licensed by Artestar, New York)

Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat is currently featured in two exhibitions: The Unknown Notebooks at the Brooklyn Museum and Now’s the Time at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), both organized by internationally renowned curator and Basquiat scholar Dieter Buchhart. At the Brooklyn Museum, Basquiat’s notebooks are consciously aligned with the work of other contemporary thinkers of color on view: Kehinde Wiley, Chitra Ganesh, and Zanele Muholi. The Toronto retrospective is an expansive outline of Basquiat’s career, featuring nearly 100 pieces and soundtracked by other diverse black innovators, among them Grace Jones and Charlie Parker. The most irreverent and prominent voice playing in the background is that of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., from his “I Have a Dream” speech.

* * *

Canada has never had a Jean-Michel Basquiat retrospective before now. This, coupled with Toronto’s reputation for diversity and Canada’s obscured relationship with systemic racism, positions the city as a kind of final frontier for a black American artist. Buchhart, who’s Austrian, sought to disturb the gregarious veneer of Canadian multiculturalism by constructing an elaborate introduction to Basquiat for Toronto. But “debuting” Basquiat is an enormous task that requires a carefully conceptualized strategy. Or not. How does one introduce one of the most famous black artists that everyone already knows about amid our current racial climate? The answer is unclear. It’s undeniable that the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat can stand alone. In Toronto, Bucchart opted for excess — voices of black American leaders, quotes from ‘80s pioneers on the walls, loads of art. Picture: curious and diverse crowds accessorized with earbuds, leaning into “Irony of a Negro Policeman” (1981) while scanning the wall text contributed by black Canadian academics. It is interesting what commodity can do.

As a black American artist, I found the exhibition disorienting. There were olive branches for American racism — the MLK dream narrative playing in the background, like the musical loops of childhood carousels — but the show could have delivered Basquiat’s political themes of centralizing black life and art with more fluidity and less excess. I was tired by the end, oversaturated by an amusement park of blackness. Such idolatry sensationalizes the organic productivity of black people. Commodity seems to be the only way that audiences can engage with our unique voices. We must be bigger than life. We must be impenetrable dreamers. Or the flip side, when black vulnerability incites fear: we must be destroyed. Both violently divorce us from freedom. There is a space for introduction, but there must also be a maintenance of authenticity.

I am unsure in what context one could consider a curator an ally. Someone who takes an interest in black artists by walking us to the front, making sure we all have a good seat. Now’s the Time is a well-intended art history lesson determined to normalize Basquiat, but instead it succeeds at making him into a caricature.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, “A Panel of Experts” (1982), acrylic and oil paintstick and paper collage on canvas with exposed wood supports and twine, 152.4 x 152.4 cm, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Gift of Ira Young (© Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat / SODRAC [2014], licensed by Artestar, New York)

I think we grow up, as black folks hearing that, in a way, we’re body, we’re not mind. So that there’s a struggle around the intellect versus the body. And here, what I see, is a peeling back of the physicality to show the intense amounts of negotiations taking place at a cerebral level. The place in which the individual is constantly negotiating external understandings of one’s self. And this happens in terms of identity making, whether or not one is black or white, or how one is racialized.

The dilemma of the show is summed up in a quote by Basquiat, advertised on a billboard in Toronto, chiding white supremacy: “I don’t want to be a black artist, I am an artist.” This long-requested dimensionality is exemplified in the painting “Dark Milk” (1986), which I didn’t recall seeing before and which is on view at AGO.

In the piece, the divide between art and racialized art is shown as an aggressively internal struggle: dueling black and brown heads spew pain upwards and downwards. Images of birds and of Basquiat’s own work anchor this unrest. “Dark Milk” clarified the convoluted thesis of the exhibition: Basquiat’s struggle with fame and self-expression. Near the top right corner of the painting, a small profile serves as the artist’s emotional specter, a red-eyed and brown-skinned skull, suffocated by his multiple identities.

* * *

“The black person is the protagonist in most of my paintings. I realized that I didn’t see many painting with black people in them.” —Jean Michel Basquiat

Back in Brooklyn, The Unknown Notebooks offers recourse for US audiences. In this exhibition, Buchhart manages to present Basquiat’s subjectivity as central, briefly unseating the myth of the black hero.

Basquiat’s notebooks share a metaphysical glimpse of the intuition of an artist whose intent was to live forever. They are profoundly expositional word collages teething on the pages of composition notebooks. The lines meant to balance text float into the background, leaving us with a score of curated misspellings and dripping jazz:

colors with numbers on the back

brooming into mezzo/aspuria

brooming into mezzo/aspuria

Eight of his notebooks are displayed in a vaulted diorama of paper, canvases in the round, and ink drawings. There is a direct sense of agency, informed by Basquiat’s black protagonist. I am reminded of Audre Lorde’s agency. In her memoir Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, she describes “that ridiculous yellow paper with those laughable wide spaces” where she drops the “y” from her name because she prefers the image of the two ending “e”s: AUDRE LORDE. Black rebellion is art.

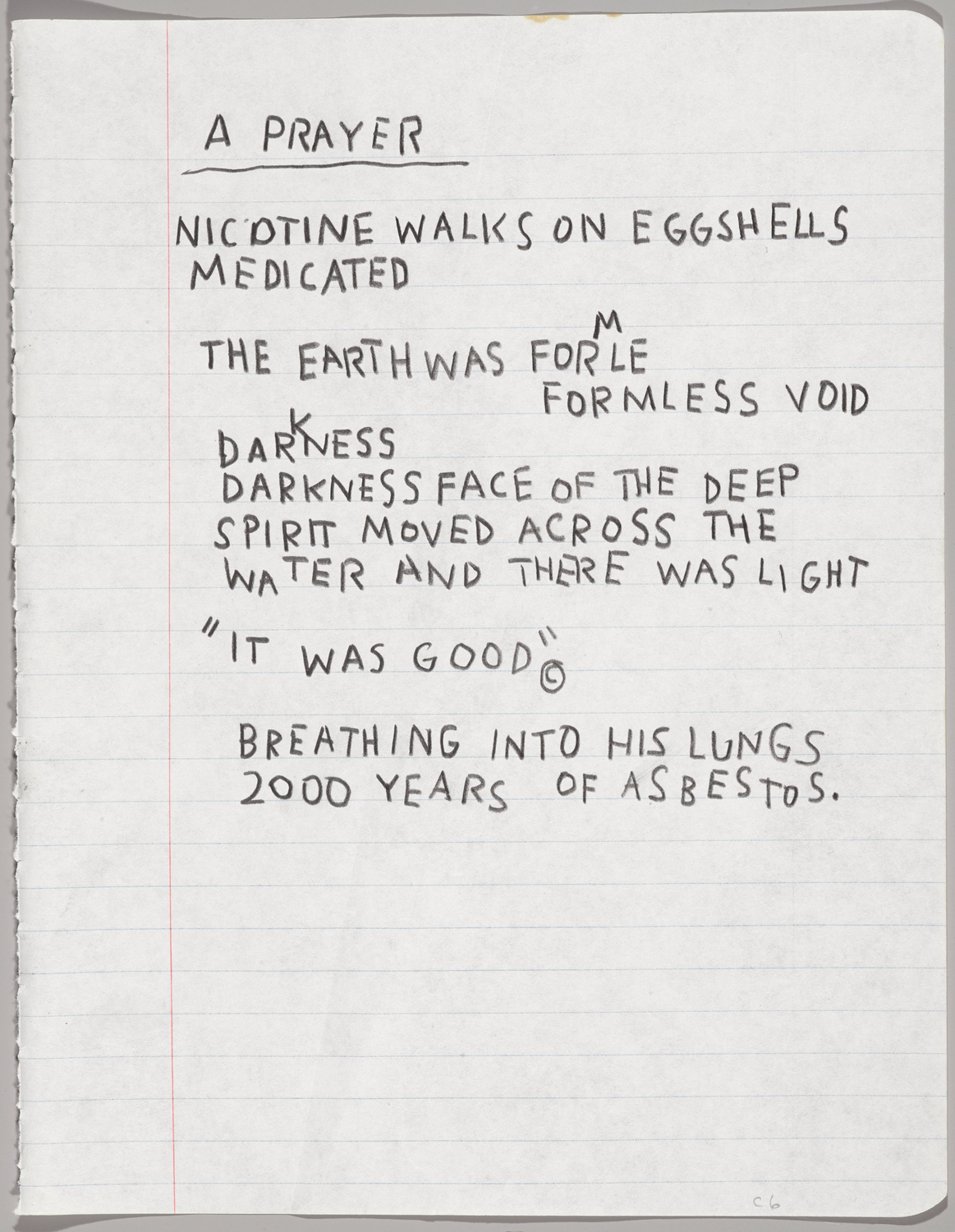

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled Notebook Page (c. 1987), wax crayon on ruled notebook paper, 9 5/8 x 7 5/8 in (24.5 x 19.4 cm), collection of Larry Warsh (photo by Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum, © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, all rights reserved, licensed by Artestar, New York)

In a notebook excerpt titled “A Prayer,” Basquiat deconstructs the Biblical Genesis, replacing Adam and the spirit of the earth with nicotine and asbestos. This prayer does not mention God, instead speculating about the question of destiny. “It was good” stands firm as a quote from scripture, but Basquiat brands the words as if they were his own. It reads as it must have been recalled — sounds shaped by memory, words shaped by sounds. One observes the deliberate spacing, marking graceful entrances for inner monologue and self.

what about this modern education

flashcards and all that.

flashcards and all that.

When black people are able to liberate ourselves from what we are told about blackness, decreasing our invisibility becomes possible. We conjure our notebooks, fashion our clocks, record art in honor of the lives that we choose. This is how we survive otherness. This is how we render ourselves immortal. That is, until our yearning abruptly ends, or is destroyed — Basquiat died of a heroin overdose in his studio at the age of 27. What did Michael Stewart and Freddie Gray leave behind? How will they be remembered? Imagine what you would write if you thought no one was looking. Imagine what you would write if you hoped everyone was.

I know one day I’ll turn the corner and I won’t be ready for it.

Installation view, ‘Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks’ at the Brooklyn Museum (photo by Jonathan Dorado, courtesy the Brooklyn Museum

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time continues at the Art Gallery of Ontario (317 Dundas Street W, Toronto) through May 10. Basquiat: The Unknown Notebookscontinues at the Brooklyn Museum (200 Eastern Parkway, Prospect Heights, Brooklyn) through August 23.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário